See Registering Property data here.

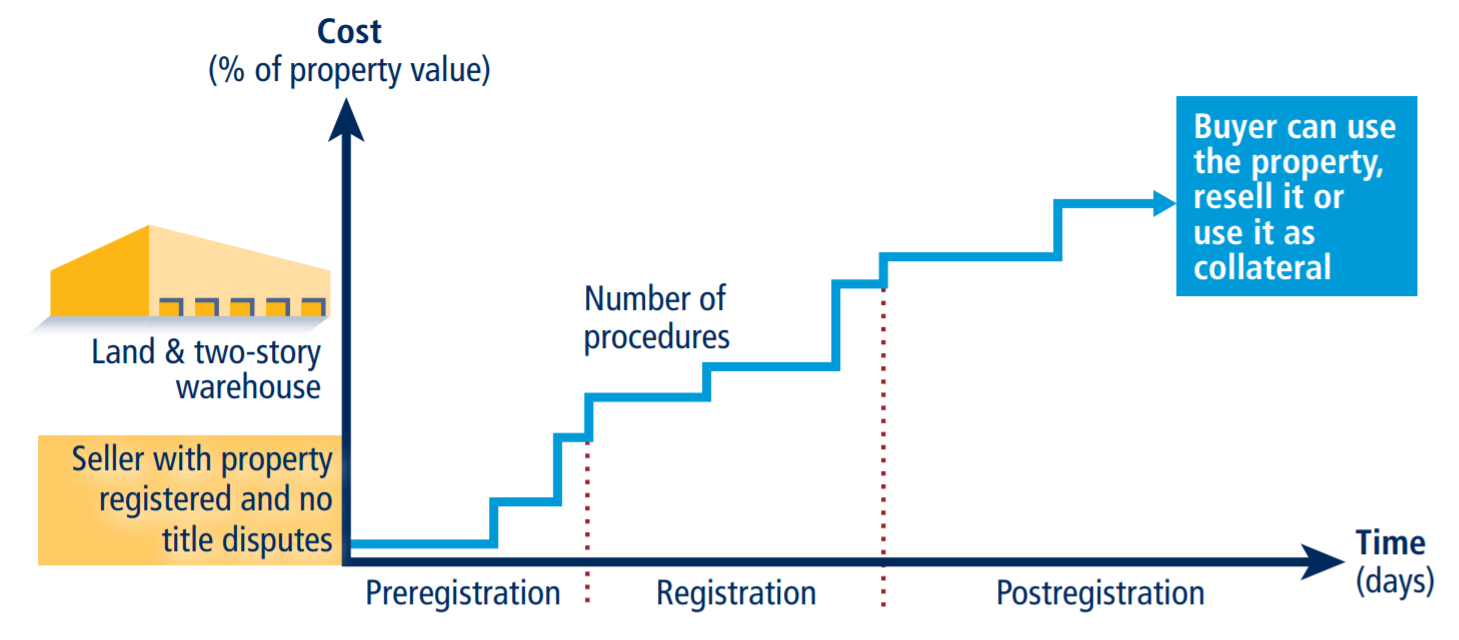

Doing Business records the full sequence of procedures necessary for a limited liability company (the buyer) to purchase a property from another business (the seller) and to transfer the property title to the buyer’s name so that the buyer can use the property for expanding its business, as collateral in taking out new loans or, if necessary, to sell the property to another business. It also measures the time and cost to complete each of these procedures. Doing Business also measures the quality of the land administration system in each economy. The quality of land administration index has five dimensions: reliability of infrastructure, transparency of information, geographic coverage, land dispute resolution and equal access to property rights.

Efficiency of transferring property

As recorded by Doing Business, the process of transferring property starts with obtaining the necessary documents, such as a recent copy of the seller’s title if necessary and conducting due diligence as required. The transaction is considered complete when it is opposable to third parties and when the buyer can use the property for expanding his or her business, as collateral for a bank loan or resell it. Every procedure required by law or necessary in practice is included, whether it is the responsibility of the seller or the buyer or must be completed by a third party on their behalf. Local property lawyers, notaries and property registries provide information on procedures as well as the time and cost to complete each of them.

To make the data comparable across economies, several assumptions about the parties to the transaction, the property and the procedures are used.

Assumptions about the parties

The parties (buyer and seller):

- Are limited liability companies (or their legal equivalent).

- Are located in the periurban (that is, on the outskirts of the city but still within its official limits) area of the economy’s largest business city. For 11 economies the data are also collected for the second largest business city.

- Are 100% domestically and privately owned.

- Perform general commercial activities.

Assumptions about the property

The property:

- Has a value of 50 times income per capita, which equals the sale price.

- Is fully owned by the seller.

- Has no mortgages attached and has been under the same ownership for the past 10 years.

- Is registered in the land registry or cadastre, or both, and is free of title disputes.

- Is located in a periurban commercial zone (that is, on the outskirts of the city but still within its official limits), and no rezoning is required.

- Consists of land and a building. The land area is 557.4 square meters (6,000 square feet). A two-story warehouse of 929 square meters (10,000 square feet) is located on the land. The warehouse is 10 years old, is in good condition, has no heating system and complies with all safety standards, building codes and other legal requirements. The property, consisting of land and a building, will be transferred in its entirety.

- Will not be subject to renovations or additional construction following the purchase.

- Has no trees, natural water sources, natural reserves or historical monuments of any kind.

- Will not be used for special purposes, and no special permits, such as for residential use, industrial plants, waste storage or certain types of agricultural activities, are required.

- Has no occupants, and no other party holds a legal interest in it.

Procedures

A procedure is defined as any interaction of the buyer, the seller or their agents (if an agent is legally or in practice required) with external parties, including government agencies, inspectors, public notaries, architects, surveyors, among others. Interactions between company officers and employees are not considered. All procedures that are legally or in practice required for registering property are recorded, even if they may be avoided in exceptional cases. Each electronic procedure is counted as a separate procedure. Payment of capital gains tax can be counted as a separate procedure but is excluded from the cost measure. If a procedure can be accelerated legally for an additional cost, the fastest procedure is chosen if that option is more beneficial to the economy’s score and if it is used by the majority of property owners. Although the buyer may use lawyers or other professionals where necessary in the registration process, it is assumed that the buyer does not employ an outside facilitator in the registration process unless legally or in practice required to do so.

Time

Time is recorded in calendar days. The measure captures the median duration that property lawyers, notaries or registry officials indicate is necessary to complete a procedure. It is assumed that the minimum time required for each procedure is one day, except for procedures that can be fully completed online, for which the time required is recorded as half a day. Although procedures may take place simultaneously, they cannot start on the same day (again except for procedures that can be fully completed online). It is assumed that the buyer does not waste time and commits to completing each remaining procedure without delay. If a procedure can be accelerated for an additional cost, the fastest legal procedure available and used by the majority of property owners is chosen. It is assumed that the parties involved are aware of all requirements and their sequence from the beginning. Time spent on gathering information is not considered. If time estimates differ among sources, the median reported value is used.

Cost

Cost is recorded as a percentage of the property value, assumed to be equivalent to 50 times income per capita. Only official costs required by law are recorded, including fees, transfer taxes, stamp duties and any other payment to the property registry, notaries, public agencies or lawyers. Other taxes, such as capital gains tax or value added tax (VAT), are excluded from the cost measure. However, in economies where transfer tax can be substituted by VAT, transfer tax will be recorded instead. Both costs borne by the buyer and the seller are included. If cost estimates differ among sources, the median reported value is used.

Quality of land administration

The quality of land administration index is composed of five other indices: the reliability of infrastructure, transparency of information, geographic coverage, land dispute resolution and equal access to property rights. Data are collected for each economy’s largest business city. For 11 economies the data are also collected for the second largest business city.

Reliability of infrastructure index

The reliability of infrastructure index has six components:

- In what format land title certificates are kept at the immovable property registry of the largest business city of the economy. A score of 2 is assigned if the majority of land title certificates are fully digital; 1 if scanned; 0 if kept in paper format.

- Whether there is a comprehensive and functional electronic database for checking all encumbrances, caveats, charges or privileges affecting a registered property’s encumbrances. A score of 1 is assigned if yes; 0 if no.

- In what format cadastral plans are kept at the mapping agency of the largest business city of the economy. A score of 2 is assigned if the majority of cadastral plans are fully digital; 1 if scanned; 0 if kept in paper format.

- Whether there is a geographic information system (a fully digital geographic representation of the land plot) —an electronic database for recording boundaries, checking plans and providing cadastral information. A score of 1 is assigned if yes; 0 if no.

- Whether the land ownership registry and mapping agency are linked. A score of 1 is assigned if information about land ownership and maps is kept in a single database or in linked databases; 0 if there is no connection between different databases.

- How immovable property is identified. A score of 1 is assigned if both the immovable property registry and the mapping agency use the same identification number for properties; 0 if there are multiple identifiers.

The index ranges from 0 to 8, with higher values indicating a higher quality of infrastructure for ensuring the reliability of information on property titles and boundaries. In Turkey, for example, the land registry offices in Istanbul maintain titles in a fully digital format (a score of 2) and have a fully electronic database to check for encumbrances (a score of 1). The Cadastral Directorate offices in Istanbul have fully digital maps (a score of 2), and the Geographical Information Directorate has a public portal allowing users to check the plans and cadastral information on parcels along with satellite images (a score of 1). Databases about land ownership and maps are linked to each other through the TAKBIS system, an integrated information system for the land registry offices and cadastral offices (a score of 1). Finally, there is a unique identifying number for properties (a score of 1). Adding these numbers gives Turkey a score of 8 on the reliability of infrastructure index.

Transparency of information index

The transparency of information index has 10 components:

- Whether information on land ownership is made publicly available. A score of 1 is assigned if information on land ownership is accessible by anyone; 0 if access is restricted.

- Whether the list of documents required for completing all types of property transactions is made easily available to the public. A score of 0.5 is assigned if the list of documents is easily accessible online or on a public board; 0 if it is not made available to the public or if it can be obtained only in person.

- Whether the fee schedule for completing all types of property transactions is made easily available to the public. A score of 0.5 is assigned if the fee schedule is easily accessible online or on a public board free of charge; 0 if it is not made available to the public or if it can be obtained only in person.

- Whether the immovable property agency formally specifies the time frame to deliver a legally binding document proving property ownership. A score of 0.5 is assigned if such service standard is accessible online or on a public board; 0 if it is not made available to the public or if it can be obtained only in person.

- Whether there is a specific and independent mechanism for filing complaints about a problem that occurred at the agency in charge of immovable property registration. A score of 1 is assigned if there is a specific and independent mechanism for filing a complaint; 0 if there is only a general mechanism or no mechanism.

- Whether there are publicly available official statistics tracking the number of transactions at the immovable property registration agency in the largest business city. A score of 0.5 is assigned if statistics are published about property transfers in the largest business city in the past calendar year at the latest on May 1st of the following year; 0 if no such statistics are made publicly available.

- Whether maps of land plots are made publicly available. A score of 0.5 is assigned if cadastral plans are accessible by anyone; 0 if access is restricted.

- Whether the fee schedule for accessing cadastral plans is made easily available to the public. A score of 0.5 is assigned if the fee schedule is easily accessible online or on a public board free of charge; 0 if it is not made available to the public or if it can be obtained only in person.

- Whether the mapping agency formally specifies the time frame to deliver an updated cadastral plan. A score of 0.5 is assigned if the service standard is accessible online or on a public board; 0 if it is not made available to the public or if it can be obtained only in person.

- Whether there is a specific and independent mechanism for filing complaints about a problem that occurred at the mapping agency. A score of 0.5 is assigned if there is a specific and independent mechanism for filing a complaint; 0 if there is only a general mechanism or no mechanism.

The index ranges from 0 to 6, with higher values indicating greater transparency in the land administration system. In the Netherlands, for example, anyone who pays a fee can consult the land ownership database (a score of 1). Information can be obtained at the office, by mail or online using the Kadaster website (http:// www.kadaster.nl). Anyone can also easily access the information online about the list of documents to submit for property registration (a score of 0.5), the fee schedule for registration (a score of 0.5) and the service standards (a score of 0.5). And anyone facing a problem at the land registry can file a complaint or report an error by filling out a specific form online (a score of 1). In addition, the Kadaster makes statistics about land transactions available to the public, reporting a total of 34,908 property transfers in Amsterdam in 2018 (a score of 0.5). Moreover, anyone who pays a fee can consult online cadastral maps (a score of 0.5). It is also possible to get public access to the fee schedule for plan consultation (a score of 0.5), the service standards for delivery of an updated plan (a score of 0.5) and a specific mechanism for filing a complaint about a plan (a score of 0.5). Adding these numbers gives the Netherlands a score of 6 on the transparency of information index.

Geographic coverage index

The geographic coverage index has four components:

- How complete the coverage of the land registry is at the level of the largest business city. A score of 2 is assigned if all privately held land plots in the city are formally registered at the land registry; 0 if not.

- How complete the coverage of the land registry is at the level of the economy. A score of 2 is assigned if all privately held land plots in the economy are formally registered at the land registry; 0 if not.

- How complete the coverage of the mapping agency is at the level of the largest business city. A score of 2 is assigned if all privately held land plots in the city are mapped; 0 if not.

- How complete the coverage of the mapping agency is at the level of the economy. A score of 2 is assigned if all privately held land plots in the economy are mapped; 0 if not.

The index ranges from 0 to 8, with higher values indicating greater geographic coverage in land ownership registration and cadastral mapping. In Japan, for example, all privately held land plots are formally registered at the land registry in Tokyo and Osaka (a score of 2) and the economy as a whole (a score of 2). Also, all privately held land plots are mapped in both cities (a score of 2) and the economy as a whole (a score of 2). Adding these numbers gives Japan a score of 8 on the geographic coverage index.

Land dispute resolution index

The land dispute resolution index assesses the legal framework for immovable property registration and the accessibility of dispute resolution mechanisms. The index has eight components:

- Whether the law requires that all property sale transactions be registered at the immovable property registry to make them opposable to third parties. A score of 1.5 is assigned if yes; 0 if no.

- Whether the formal system of immovable property registration is subject to a guarantee. A score of 0.5 is assigned if either a state or private guarantee over immovable property registration is required by law; 0 if no such guarantee is required.

- Whether there is a specific, out-of-court compensation mechanism to cover for losses incurred by parties who engaged in good faith in a property transaction based on erroneous information certified by the immovable property registry. A score of 0.5 is assigned if yes; 0 if no.

- Whether the legal system requires verification of the legal validity of the documents (such as the sales, transfer or conveyance deed) necessary for a property transaction. A score of 0.5 is assigned if there is a review of legal validity, either by the registrar or by a professional (such as a notary or a lawyer); 0 if there is no review.

- Whether the legal system requires verification of the identity of the parties to a property transaction. A score of 0.5 is assigned if there is verification of identity, either by the registrar or by a professional (such as a notary or a lawyer); 0 if there is no verification.

- Whether there is a national database to verify the accuracy of government-issued identity documents. A score of 1 is assigned if such a national database is available; 0 if not.

- How much time it takes to obtain a decision from a court of first instance (without an appeal) in a standard land dispute between two local businesses over tenure rights worth 50 times income per capita and located in the largest business city. A score of 3 is assigned if it takes less than one year; 2 if it takes between one and two years; 1 if it takes between two and three years; 0 if it takes more than three years.

- Whether there are publicly available statistics on the number of land disputes at the economy level in the first instance court. For the 11 economies where the data are also collected for the second largest business city, city-level statistics are taken into account. A score of 0.5 is assigned if statistics are published about land disputes in the economy in the past calendar year; 0 if no such statistics are made publicly available.

The index ranges from 0 to 8, with higher values indicating greater protection against land disputes. In the United Kingdom, for example, according to the Land Registration Act 2002 property transactions must be registered at the land registry to make them opposable to third parties (a score of 1.5). The property transfer system is guaranteed by the state (a score of 0.5) and has a compensation mechanism to cover losses incurred by parties who engaged in good faith in a property transaction based on an error by the registry (a score of 0.5). In accordance with the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 and the Money Laundering Regulations 2007, a lawyer verifies the legal validity of the documents in a property transaction (a score of 0.5) and the identity of the parties (a score of 0.5). The United Kingdom has a national database to verify the accuracy of identity documents (a score of 1). In a land dispute between two British companies over the tenure rights of a property worth $2,066,500 the Land Registration division of the Property Chamber (First-tier Tribunal) gives a decision in less than one year (a score of 3). Finally, statistics about land disputes are collected and published; there were a total of 1,030 land disputes in the country in 2018 (a score of 0.5). Adding these numbers gives the United Kingdom a score of 8 on the land dispute resolution index.

Equal access to property rights index

The equal access to property rights index has two components:

- Whether unmarried men and unmarried women have equal ownership rights to property. A score of -1 is assigned if there are unequal ownership rights to property; 0 if there is equality.

- Whether married men and married women have equal ownership rights to property. A score of -1 is assigned if there are unequal ownership rights to property; 0 if there is equality.

Ownership rights cover the ability to manage, control, administer, access, encumber, receive, dispose of and transfer property. Each restriction is considered if there is a differential treatment for men and women in the law considering the default marital property regime. For customary land systems, equality is assumed unless there is a general legal provision stating a differential treatment.

The index ranges from -2 to 0, with higher values indicating greater inclusiveness of property rights. In Mali, for example, unmarried men and unmarried women have equal ownership rights to property (a score of 0). The same applies to married men and women who can use their property in the same way (a score of 0). Adding these numbers gives Mali a score of 0 on the equal access to property rights index—which indicates equal property rights between men and women. By contrast, in Tonga unmarried men and unmarried women do not have equal ownership rights to property according to the Land Act [Cap 132], Sections 7, 45 and 82 (a score of -1). The same applies to married men and women who are not permitted to use their property in the same way according to the Land Act [Cap 132], Sections 7, 45 and 82 (a score of -1). Adding these numbers gives Tonga a score of -2 on the equal access to property rights index—which indicates unequal property rights between men and women.

Quality of land administration index

The quality of land administration index is the sum of the scores on the reliability of infrastructure, transparency of information, geographic coverage, land dispute resolution and equal access to property indices. The index ranges from 0 to 30 with higher values indicating better quality of the land administration system.

If private sector entities were unable to register property transfers in an economy between May 2018 and May 2019, the economy receives a “no practice” mark on the procedures, time and cost indicators. A “no practice” economy receives a score of 0 on the quality of land administration index even if its legal framework includes provisions related to land administration.

Reforms

The registering property indicator set tracks changes related to the efficiency and quality of land administration systems every year. Depending on the impact on the data, certain changes are classified as reforms and listed in the summaries of Doing Business reforms in order to acknowledge the implementation of significant changes. Reforms are divided into two types: those that make it easier to do business and those changes that make it more difficult to do business. The registering property indicator set uses only one criterion to recognize a reform.

The impact of data changes is assessed based on the absolute change in the overall score of the indicator set as well as the change in the relative score gap. Any data update that leads to a change of 0.5 points or more in the score and 2% or more on the relative score gap is classified as a reform, except when the change is the result of automatic official fee indexation to a price or wage index (for more details, see the chapter on the ease of doing business score and ease of doing business ranking). For example, if the implementation of new electronic property registration system reduces time and procedures in a way that the score increases by 0.5 points or more and the overall gap decreases by 2% or more, the change is classified as a reform. Minor fee updates or other small changes in the indicators that have an aggregate impact of less than 0.5 points on the overall score or 2% on the gap are not classified as a reform, but the data are updated accordingly.